Book Excerpt: Guillermo Del Toro Dishes in FilmCraft: Directing

Oscar-nominated director Guillermo del Toro has been in the craft of filmmaking since he was 16, filling roles as diverse as P.A., assistant director and makeup effects. He made his first film Cronos at 28 and received his Academy Award-nomination in 2007 for Pan's Labyrinth, making him one of the most prominent filmmakers to emerge from his native Mexico. In a candid interview, he explains how he learned filmmaking in author Mike Goodridge's new book, FilmCraft: Directing.

Oscar-nominated director Guillermo del Toro has been in the craft of filmmaking since he was 16, filling roles as diverse as P.A., assistant director and makeup effects. He made his first film Cronos at 28 and received his Academy Award-nomination in 2007 for Pan's Labyrinth, making him one of the most prominent filmmakers to emerge from his native Mexico. In a candid interview, he explains how he learned filmmaking in author Mike Goodridge's new book, FilmCraft: Directing.

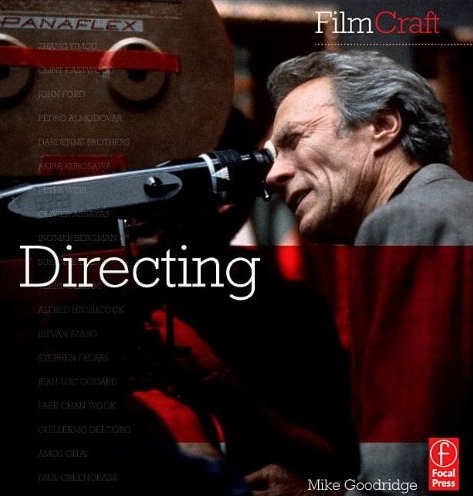

Goodridge, who until recently served as editor of Screen International and is now CEO of the international sales and financing company Protagonist Pictures wrote the book which features in-depth interviews with 16 of the world's celebrated and respected film directors including Del Toro, Clint Eastwood (Million Dollar Baby) Paul Greengrass (The Bourne Supremacy), Peter Weir (The Truman Show), Terry Gilliam (Brazil) and Park Chan-wook (Oldboy). These and other filmmakers share their insights and experiences on development, storytelling/writing, working with actors and cinematographers, as well as other areas necessary to completing a successful film.

In this excerpt from the book, which will be available via Amazon beginning June 15th, Guillermo del Toro gives his take on the mistakes and triumphs of his first movie as well as the first movie of other filmmaking greats, a life lesson courtesy of John Lennon, Tom Cruise's take on filmmaking, what made him cry during his first movie, making 'everything' theatrical and why having "enough money" will get you, err... screwed.

Director Guillermo Del Toro excerpt from FilmCraft: Directing:

I came from the provinces, from Guadalajara, which is the second largest city in Mexico and nobody makes movies there. When I was a teenager, I started building relationships in Mexico City and I started as a blue-collar member of the crew. I was either a boom guy or a PA or an assistant director. I was makeup effects. I did my floor time in both TV and movies. My first professional work on a movie was at the age of 16 and I made Cronos when I was 28, so I had twelve solid years of doing just about everything in between. If somebody needed something, I would do it. I even did illegal stunt driving. But what happened is that I learned a little bit of everything and, once you put your time into exploring everything, you get to know what every piece of grip equipment is called and how many you need, and how to do post — I edited my own movies and did the post sound effects on all of them. So to some extent, directing came naturally to me from my first movie.

My first movie Cronos is not in any way a perfect movie, but it’s a movie full of conviction. When you make your first movie, whatever mistakes you make are very glaring, but if you have conviction, and I would even say cinematic faith, this also shines through. I recently watched Cronos again and I thought, “I like this kid,” he has possibilities. After your first movie, with a little bit of craft, diligence, and more importantly, experience, you learn to make virtues out of some of your defects.

What I mean is that any first movie has good moments, even if it is not entirely perfect. It can be a filmmaker as famous as you like, such as Stanley Kubrick, whose first film Fear and Desire (1953) is about 70 minutes long and stars Paul Mazursky. It is very stilted, very awkwardly paced, full of stuff that doesn’t work, the actors speak in a patois, and it has a very non-naturalistic rhythm. But what is incredibly fascinating is that the very stilted quality, that artificial rhythm, eventually became his trademark in later films. He bypasses it in more naturalistic films like The Killing (1956) and Paths of Glory (1957), but comes back to that type of hyperrealism or strange filtered reality in his later movies, and he is in complete control of it there. Kubrick used the tools he acquired in making other films to transform what you thought was a defect in Fear and Desire into a virtue.

In my case, when I make movies in Spanish, starting with Cronos, I purposefully avoid characterizing certain things in the conventional Hollywood sense, and that comes out as a blatant defect. Specifically, I had shot a much longer film, including a whole section between the husband and wife where she noticed that he is getting younger and they start falling in love again. At night, he would come and sleep underneath her bed. But I couldn’t make it work. The way I staged it was simply too stilted and strange, and I didn’t feel comfortable leaving it as part of the movie. Even to this day, I think there is a mix of different tones in that movie. I change from the dramatic to the comedic too often. I try to do it generically, mixing horror with melodrama, and there are moments in Cronos that are really jarring for me. I sometimes allowed Ron Perlman to be too broad and it simply didn’t work. I think I did it better in my later movies.

I don’t know whether that mix of genres is my trademark. One of the things that was very influential for me when I was kid was the book by Tolkien in which he discussed fairy stories in literature. I remember him saying in that book that you should make the story recognizable enough to be rooted in reality, but outlandish enough to be a flight of fancy. So I try to mix an almost prosaic approach, or at least a rigid historical context, with fantastic elements. I treat the fantasy characters very naturalistically or else I root the story in a precise context like The Devil’s Backbone or Pan’s Labyrinth, or in Cronos, post-NAFTA Mexico.

As Tolkien says, when you give the audience a taste of what they can recognize, they immediately accept the rest of the concoction; it’s almost like wrapping a pill in bacon for a dog to swallow it. You need, for example, the bacon of domesticity in Cronos. I wanted to shoot that family as a very middle-class family in Mexico. I wanted a kitchen that looked like a kitchen you’d recognize, a really ordinary bedroom and very mild, neat clothing design. Out of that middle-class reality, I wanted a single anomaly — the mechanical clockwork scarab device.

If the audience believes that this abnormality is as real as it can be, they will respond to the story. Many directors think that the more you keep the creature in the shadows and don’t show it, the better it is, but I don’t believe that. I don’t have monsters in my movies, I have characters, so I shoot the monsters as characters. For example, in Hellboy, I shot Abe Sapien, the fish-man, like any other actor. I didn’t fuss about it, I shot the monster with the same conviction that I would shoot Cary Grant or Brad Pitt; in other words, if I shot it in a different way than I would the regular actors, I would be making a mistake.

What I do in every movie very consciously is to ensure that this anomaly is shot two notches above actual reality, so it’s weird enough to accommodate the monster, but not too stylistic that it’s unrecognizable. For example, everything you see in Pan’s Labyrinth — the house, the furniture — is fabricated to be slightly more theatrical than it needed to be. The uniforms for the captain and his guards are exactly what were worn at the time, but we tweaked the cut and the collar to make them more theatrical. Everything around the creatures, therefore, exists like a terrarium for them to live in so that when it comes to shoot them, I can shoot them in a normal way.

I was very nervous on Cronos, but the adrenaline carried me through. Directing is almost like keeping four balls in the air on a monocycle with a train approaching behind you. There were days, for example, like the scene with the husband sleeping under the bed, where I knew I’d fucked up. The makeup was wrong and we didn’t have time to go back and change it, we didn’t even have time to test it. The light was wrong. Everything was wrong, and I arrived home to my wife that night and cried. I said that I had destroyed the scene I had dreamt of for years. I didn’t have the luxury of reshoots. Of course, you can only break down in front of your wife, or your partner, or your parents. In front of the staff on the film, you need to keep total control. You don’t want anyone thinking the general is afraid—you have to be leading the charge. There are two very lonely positions on a movie set: the actor and the director. The cinematographer has a close liaison with the director, the gaffer, the grip, etc. The director is alone on one end of the lens and the actor is alone on the other. That’s why the great, most satisfying partnerships on set are when a director and actor come to love and support each other.

Being from Mexico is an enormous part of who I am as a filmmaker. The panache, the sense of melodrama, and the madness I have in my movies that allows me to mix historical events with fictional creatures, all comes from an almost surreal Mexican sensibility. I’m really prone to melodrama. This comes from watching Mexican melodrama obsessively, to the point where I was watching The Devil’s Backbone with a Spanish architect and the architect said to me that it was more Mexico than Spain; the characters were acting like Latin characters. If my father hadn’t been kidnapped in 1998 then frankly I would be making Mexican movies interspersed with the European and American. Since 1998, I cannot go back to Mexico because I would be too visible a target, especially when there is a printed schedule of where I am going to be every day for the entire run of a shoot.

I think of the audience every second during writing; I think of them as me. I question how I would understand something, or what would make me feel a certain way. When I’m shooting a scene that moves the characters, I weep, I feel the emotion on set, so when I am writing it, if it doesn’t work, I don’t print it out until I have that feeling. Creating tension is a different skill to creating fear. For fear, you try to create atmosphere. You ensure the scene is alive visually before anything is added, then you craft the silence very carefully because silence often equals fear.

Rarely can you elicit fear with music unless the music is used very discreetly, underlining the scene in a way that is almost invisible. When the Pale Man appears in Pan’s Labyrinth there is music, but Javier [Navarrete, the film’s composer] is almost just underlining his movements. It becomes like a sound effect. Silence is one of the things that you learn to craft the most because there is never real silence in a movie; you always have distant wind, cars, dogs barking, or crickets in the distance. I think really well-crafted silence creates tension, and by the same token an empty frame, an empty corridor for example — if it’s empty in the right, creepy way — is a tool.

You know if a scene’s not working on set, and as you get older and craftier, you can learn to re-direct it in post. You can patch it up in your coverage and recover it—you can even end up with a great scene because beauty rarely comes out of perfection. For something to work, I think it has to come out of emotional turmoil. You can’t encapsulate the perfect melody; a huge component of it is instinctive.

Then, of course, there are the actors. Many times you storyboard and rehearse with the actor, and then you come to the scene and it’s not working. But then you try something different and something suddenly happens that makes it work. It’s very raw. It’s funny, we enthrone this idea of the perfect filmmaker, this myth of the all controlling, all-seeing, all-encompassing person, but even for Kubrick or von Stroheim there is a part of the process that is entirely instinctive. I once asked Tom Cruise about it and he confirmed that Kubrick often found things in a panic on Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

I love imperfection. I have been friends with James Cameron since 1992 and because he is so incredibly precise, people sometimes don’t think he is human, but the beauty of being a close friend is that I’ve seen him burn the midnight oil and toil and sweat. These imperfections in the façade are what make the work more admirable. Art depends on that human touch that doesn’t make perfection; in fact the filmmakers and films I am most attracted to require a level of human imperfection.

On the big effects films, you try to prepare thoroughly but there are always surprises. John Lennon said, “Life is what happens when you are making other plans” and I think film is what happens when you are making other plans. You come onto the set and either the actor or the material doesn’t come out as you expect and the film comes out better for it. If you have either experience or inspiration, one of the two will get you through. One you accumulate through the years, the other you cherish.

As a young filmmaker you’re full of inspiration and if you are unlucky you are only trading it in for experience. You need to remain on dangerous ground to continue to be inspired. I am always tackling things I shouldn’t tackle and meddling with stuff I shouldn’t meddle with. You never have enough money. If you ever feel one day you have enough money, that’s the day you’re fucked.

FilmCraft: Directing is available via Amazon beginning June 15th.

Follow Movieline on Twitter.