REVIEW: Epic Marley Revels in the Life, Music and Secrets of Bob Marley

The best documentaries tell you more than you think you’d ever want to know about a subject, perhaps fulfilling a curiosity you didn’t know you had. That’s the case with Kevin Macdonald’s Bob Marley documentary Marley, which stretches out at a languorous two hours and 24 minutes without dragging or getting bogged down in extraneous details. Everything in it – from interviews with the singer’s bandmates and his widow, Rita, to vintage and contemporary images of his hardscrabble birthplace of St. Ann Parish, Jamaica, to live-performance footage that captures his extraordinary charisma – feels essential, albeit in a relaxed way. By the end you feel you’ve learned something about the man, yet his mystique emerges intact.

Robert Nesta Marley was born in 1945, to an Afro-Jamaican mother, Cedella, and a much older white Jamaican father, Norval Sinclair Marley, who was of English descent and who barely played a part in young Robert’s upbringing – he’d visit the family occasionally, but he was a shadowy figure who, as it turns out, also fathered a child by another Jamaican woman. Macdonald grounds Marley’s story firmly in a sense of place, using simple images for whopping impact: A black-and-white still photo shows Marley’s childhood home, which is essentially a shack with a few windows. When Marley was 12, his mother moved her little family to the Trench Town area of Kingston, in an effort to build a better life. One of Marley’s childhood friends recalls that that type of “better life” often included going to bed hungry. Kids heard the words “Drink some water and go to bed” a lot, simply because there was nothing else their parents could do for them.

Despite growing up amid that kind of hardship — or maybe partly because of it — Marley always loved music and always found ways to make it, and Macdonald does a superb job of outlining a mini-history of ska and reggae, musical forms built in the early 1960s from the spontaneous mingling of Caribbean rhythms and American pop music. One of Marley’s childhood friends described the home-made instruments used to make this music in its most rudimentary form: A box with rigged with strings known as a rhumba box; drums made from cow skin; and the instrument referred to by this fellow as the “shake-shake,” which really needs no explanation. Marley and his friends listened to American acts like the Platters, the Drifters and the Temptations, and after Marley made his first recording, in 1962 – a pseudo-spiritual called “Judge Not” – he became part of the band that came to be known as the Wailers. The group rehearsed for two years before the producer at their local recording studio allowed them to make a record: In the meantime, they played not just in town squares but also in cemeteries, to ward off evil spirits – if you could placate those guys, you’d be able to perform without fear in front of anybody.

Macdonald arranges his material in a way that’s chronological though not strictly linear, covering a lot of territory with an easygoing cross-thatching of stories of interviews: Marley’s gradual but steady rise from ambitious, talented writer and musician to revered cult figure; his embrace of Rastafarianism; his association with legendary producer Lee "Scratch" Perry (shown, in contemporary footage, looking and acting extremely wiggy) and Island Records founder Chris Blackwell; and, last but not least, his propensity for consuming somewhere near a pound of marijuana a day. (Did I dream that, or is it actually in the documentary? Either way, he smoked a lot.) Most illuminating are the interviews Macdonald conducted with Bunny Wailer, founder and original member of the Wailers (who holds court before the camera, resplendent in dark glasses and a puffy zebra-striped hat), and Rita Marley, who tells how, at the height of her husband’s fame, she’d sometimes be called in to dispatch his extracurricular girlfriends from his dressing room. (She’d march in, announcing to everyone that it was time for bed.)

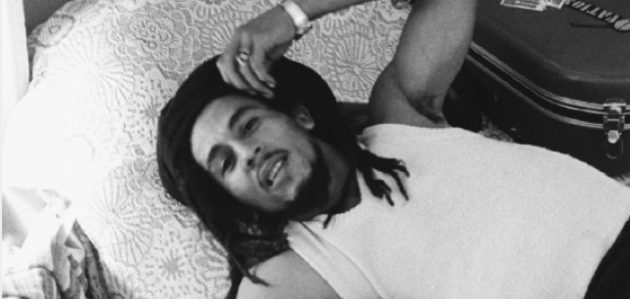

Marley had a lot of extracurricular action, including a longtime relationship with former Miss World Cindy Breakspeare, who’s interviewed at length in the film. We learn that he fathered 11 children by seven different mothers during his lifetime. (One woman interviewed in the film is identified only as “Baby Mother.”) He died of cancer, in 1981, at age 36 – Macdonald handles the details of his death so matter-of-factly that it might not hit you until later how poignant they are. At one point his daughter, who clearly harbors a lot of resentment toward her free-spirited absentee father, remarks on his appearance after the progression of his illness required him to cut off his heavy dreadlocks: “He looked, like, so tiny.”

If Marley lived the high life, sometimes at others’ expense, it’s worth noting that the women around him who lived to tell the tale – Rita Marley, Breakspeare and backup singer Marcia Griffiths – look remarkably youthful: No wrinkles, no cry. Macdonald clearly has a great deal of respect for his subject, and maybe even some reverence. But he doesn’t pretend that Marley’s great talent and charm existed in a vacuum – every minute, he’s finding a new context for the man’s career and life, and the portrait he ultimately comes up with is prismatic and fascinating. With pictures like The Last King of Scotland and State of Play, Macdonald has proved such an adept fiction filmmaker that it’s easy to forget he made documentaries for years, including Touching the Void and the Oscar-winning One Day in September. In that respect, Marley is a homecoming of sorts. It’s at once leisurely and controlled, like a Bob Marley song, with fresh secrets in every groove.

Follow Stephanie Zacharek on Twitter.

Follow Movieline on Twitter.

Comments

Bob Marley's mother's name was Cedella, which is also the name he gave his eldest daughter by birth, not Cedelia.

Duly noted. Thank you!

i really loved the in-depth look at marleys life ... also, while watching it on Facebook i saw that the house of marley has a 15% off deal if you buy something with the promo code:marleymovie. the Facebook has more info http://on.fb.me/JUqSWE. enter the code at http://www.thehouseofmarley.com.

Finally bob accepted Jesus christ.