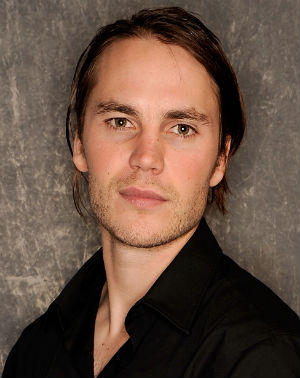

Taylor Kitsch on The Bang Bang Club, Honoring Fallen War Photographers, and Battleship

There's a heartbreaking relevance to this week's historical drama The Bang Bang Club, based on the true story of four photographers who risked their lives to cover the brutalities of civil war in apartheid-era South Africa; like photojournalists Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, both tragically killed this week in Libya, two of the four founding members of the so-called club fell victim to the violence they fought to bring to the world's attention. Days before Hetherington and Hondros died, Movieline spoke with actor Taylor Kitsch about the responsibility of portraying real-life South African photojournalist Kevin Carter and the risks Carter and his colleagues took, emotionally and physically, in the line of duty.

There's a heartbreaking relevance to this week's historical drama The Bang Bang Club, based on the true story of four photographers who risked their lives to cover the brutalities of civil war in apartheid-era South Africa; like photojournalists Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, both tragically killed this week in Libya, two of the four founding members of the so-called club fell victim to the violence they fought to bring to the world's attention. Days before Hetherington and Hondros died, Movieline spoke with actor Taylor Kitsch about the responsibility of portraying real-life South African photojournalist Kevin Carter and the risks Carter and his colleagues took, emotionally and physically, in the line of duty.

In the film, director Steven Silver tackles the ethnic black-on-black violence that erupted in a divided South Africa towards the end of apartheid as seen through the lenses of real-life photographers Kevin Carter (Kitsch), Greg Marinovich (Ryan Phillippe), Joao Silva (Neels Van Jaarsveld), and Ken Oosterbroek (Frank Rautenbach). Based on the non-fiction book The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots from a Hidden War (co-written by Marinovich and Silva - the two remaining members of the group) The Bang Bang Club pulls few punches when it comes to the violent images of war, many recreated from actual photographs, that these men captured up close on film.

[Spoilers follow]

In real life, Kevin Carter hit rock bottom due to substance abuse (a coping mechanism for the emotional trauma and stress of the job, the film suggests) and traveled to Sudan in 1993 to photograph a U.N. humanitarian mission. A resulting photograph depicting a starving Sudanese girl being stalked by a vulture won him the Pulitzer Prize for photojournalism but courted controversy over the girl's subsequent fate, leading to debates over a journalist's moral obligation to intercede on behalf of their subject. Weeks after winning the Pulitzer, Carter's friend Oosterbroek was killed in the line of duty. A few months later Carter took his own life.

Kitsch, needless to say, felt an extreme responsibility to honor not only Carter's life and legacy but the lingering emotional scars of the people who lived through the horrific and senseless violence of apartheid. He spoke of the high stakes, personal risks, and difficulties of returning to normal life after undergoing arguably the hardest role of his career -- and how his next films, 2012's John Carter of Mars and Battleship, presented their own new challenges.

The Bang Bang Club is available on VOD now and opens in limited release on April 22.

You've said that part of the appeal of playing Kevin Carter was that it scared you. What was that fear all about?

Man, so many things from a personal standpoint. I think the biggest thing that scared me was doing what it takes to play this cat honestly because the stakes are so high. It's a true story. Going there and working with the guys he actually worked with, the two remaining Bang Bang Club members, and just taking that challenge. I mean, if you take on a project and you're like, "I'm gonna kill this," where's the risk? Where's the challenge? I think that's what makes you prep so much; that's what makes you push the envelope and do whatever you can to play this guy honestly. Because everyone that is going to watch you is going to go, "Oh, that's who Kev Carter was." You can derive so many assumptions through the way I play him, so you take that to heart.

This film in particular carries many different responsibilities in its execution. On one hand, it's autobiographical, but there's also the devastatingly violent larger conflict that it portrays. And you filmed on location in the townships where these events actually happened, so it seems especially important to pay respect as you're telling this story.

I think so. Even doing this film... of course it's an escape, it's a film. But being that this is such serious content, for me personally the way I took it was that I keep going back to just doing this honestly. I didn't play Kev certain ways in certain scenes to entertain. If I was honest to who I felt he was in these situations, that alone was going to be entertaining. Because this guy, to me, was an incredible guy; an empathetic, endearing guy with a great sense of humor. And to show that whole spectrum was the challenge.

Within this group of photojournalists, Kevin's the one through whom you most feel the impact of this lifestyle and this job and this war. It's sort of strange to talk about what happens to this character because clearly we know what really happened to him in real life, but under normal fictional circumstances that might be considered a spoiler.

Yeah, I mean, it's up to you. Him taking his own life is something that, if you know anything about these guys, you know it's inevitable. But I think the journey there is what's intriguing.

What aspects of that journey engaged you most? A few facts are most widely known about the real Kevin: His famous Pulitzer-winning photograph of the Sudanese girl and the vulture, and how he subsequently took his own life.

Therein lies the challenge! You Google, YouTube the cat and it's about the drugs, the mandrax -- that intense drug that you take and it's more powerful than heroin. And it's like that's what Kev's remembered by, and him breaking from that vulture shot. So it's my job, I felt, with the scenes given and his arc, to show the whole spectrum of him. And by the way, you'd get quite bored if you just watched me do drugs in every scene. I think the reason why you do it is a lot more important than the sake of doing it, and that as an actor was the challenge as well.

Kevin has a line in the beginning in which he advises Ryan Phillippe's character to ditch his long lens --

"It only looks good up close."

Yes, exactly. And that, of course, is a metaphor for the emotional distance that these guys had to their subjects.

Glad you picked up on that.

So that's how we're introduced to Kevin. He seems somewhat cavalier about the job, at least at first.

I think, too, just an open, exciting guy. "Oh, a new guy? I want to meet him!" That's who Kev was.

At what moment do you think that the constant immersion in tragedy and violence, the emotion and moral conflicts inherent to a war photographer's work, began to chip away at him?

I think the big one was, for me, where you take him out of his element. Where you take everything he lives for in that moment, you take his three best friends from him. You fire me, I've got nothing left to live for. I've got my daughter, which was a huge thing for Kev that not many people know. I put a tattoo [above his heart] of Megan - MC. He didn't have that, but I put that on there for her, who I met while I was working there as well. But I think that was the biggest thing that started his downfall. It was sort of a wake-up call. Then you go to Sudan and take that picture, and even during that picture what it was that crushed Kev was that he saw the lack of a father to his daughter. There's a string on his wrist that falls down that was something that his daughter gave him. That was a little thing I had. I think that really started his fall.

Kevin's also one of the characters who most clearly embodies a dominant issue in the film and in photojournalism: The line between helping a subject and exploiting their pain, or keeping a necessary distance when people are being killed literally in front of you.

Greg Marinovich as well, in the film. It really is an endless debate -- the vulture shot, the moral ground that you stand on when you take pictures. And Joao [Silva] told me in South Africa, because we would have these debates, quite heated, on set. I think a lot of it is that you put other people in jeopardy, too, when you take so many things upon yourself in the heat of the moment. You've got to recognize that as well, because there are people there to do that job, and once you're trying to do this vigilante shit of saving everyone and getting a photo, then it's just utter chaos. And in those situations we already have so many people scared shitless. The police that were there at Ken Oosterbroek's death weren't even trained, and it was friendly fire that shot him - a cop shot him because they panicked. So that's a perfect example. I think it takes a lot more to know where you stand in that situation than to just grabbing straws and panicking. Because someone else is going to die, if not you. It's a fine line, like you said.

Do you see parallels between the moral conflict of the combat photojournalist, whose livelihood depends on getting footage of others' suffering, and going yourself as a filmmaker into Johannesburg to make a feature film about these events?

I guess so, but we're telling a story and raising awareness. Hopefully, if anything, you're going to be educated about apartheid and what these guys did and represented. That's my motivation, and it really doesn't go farther than that. The challenge as an actor to get there and do that, it is very similar.

Pages: 1 2

Comments

Loved the interview.

His haircut is strange.

America's great white hope in actually producing a homegrown action hero as opposed to stealing them all from Australia.

Sorry to say but he's canadian!

Btw great interview! I love the passion he has for the craft and the characters he plays.