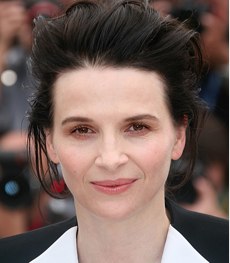

Juliette Binoche on Certified Copy, Minimum French and Watching Godard Search

Juliette Binoche's latest film, Certified Copy, offers a bit of everything for the discriminating cinemagoer: the famously exact and entrancing mise en scene of Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami; the sanguine folkways of Tuscany; humor, sophistication and not just a little mindbending heartbreak in the tale of an Englishman (opera veteran and film newcomer WIlliam Shimell) and Frenchwoman (Binoche) meeting for the first time (or are they old lovers finally dissolving?); and of course Binoche herself, an international icon who nevertheless needed nearly 15 years to fulfill her goal of working with Kiarostami.

Juliette Binoche's latest film, Certified Copy, offers a bit of everything for the discriminating cinemagoer: the famously exact and entrancing mise en scene of Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami; the sanguine folkways of Tuscany; humor, sophistication and not just a little mindbending heartbreak in the tale of an Englishman (opera veteran and film newcomer WIlliam Shimell) and Frenchwoman (Binoche) meeting for the first time (or are they old lovers finally dissolving?); and of course Binoche herself, an international icon who nevertheless needed nearly 15 years to fulfill her goal of working with Kiarostami.

In a long conversation with Movieline last fall, Binoche elucidated the back story behind the terrific Certified Copy -- the film for which she won last year's Best Actress prize at Cannes and which finally opens Stateside this week in limited release. (It's available March 23 on VOD via IFC.) As usual, it's best left to her to explain, as with her tales of Jean-Luc Godard, Michael Haneke, working with screen rookie Shimell, and what made doing her own driving in the film a "nightmare."

The story about you meeting Kiarostami in Tehran is so great, but I've only read it condensed and second-hand. Could my readers and I hear it in your own words?

At the Cannes Film Festival, I had an idea of doing interviews with directors-- about this relationship between directors and actor. I found it fascinating how that kind of combination happens. And at the end of the interview with Abbas Kiarostami, he said to me, "It's a very bad idea, this interview. Come to Tehran; it's much better." So I thought, OK! Going to Tehran is not the first thing you think about when you live in the Western world. First of all, there was all this big drama between Iran and the West and France.

This was two years ago? Three years ago?

About three years ago. Things were very tense. Finally -- a year after, I think -- I wound up having some time off, and I wound up going. I asked for a visa, and I got my via; I was surprised it would work out. Also, I was surprised: As Abbas was saying, "It's easy there. Come, you'll see it's not at all what people say." So I was curious. And it just happened that when I came out of the plane, there were photographers and video people taking pictures of Abbas and myself. And I was thinking, Why did you do that? We don't need publicity! I'm just coming as a friend discovering Iran -- not as an actress! And he was thinking, Why did she do that? We didn't need that! Why did she put this press around us?

It just happened that on board the plane, there was a journalist who phoned his friends and said, "Hey, Juliette Binoche is on the plane. Make sure you have some photographers and cameras on the ground, blah blah blah." So the next day we're on the front of this New Yorker, Le Mans, kind of intellectual newspaper, and then suddenly they announce we have a project together. And we didn't! We didn't have any project together. And finally Abbas says, "This is a problem, because this is not true, first of all. For my government, I don't know how this will be taken. So it's better to deny and say the truth: We don't have any projects, and you're just coming as a friend."

So I did two days of interviews saying we don't have a project, I just met him several times on different occasions... We don't even know each other that well. At the end of the second day of interviews, finally Abbas started to tell me about this story that happened to him in Italy. He described giving a lot of details spoken in English, and at then end of it, he probably made up some stories because he could see me completely drawn into his situation. At the end, he said, "Do you believe me?" And I said, "Yes, of course." And he said, "Well, it's not true."

And then I started laughing because I could not believe he had taken me on that journey as a fairy tale. A few days later, I was still laughing about it, and it just so turned out that we went to Isfahan, this well-known city with all these mosques from, I think, the 16th century. His cameraman was there, and I was kind of dozing -- lagging behind, tired, just finished filming or something. And then I heard Mahmoud laugh, and I kind of woke up and said, "You're telling the moment of..." This, this, this, and that. And they were talking in Farsi; they were amazed I could figure it out and tell why he was laughing. And Mahmoud said, "You've got to make that film."

So I signed the contracts in the car, with fingerprints. Abbas and myself signed. And before I went back to Paris, he said, "Find a producer." I found a producer, and we made the film. He wrote the script a year after, and we shot it a year after [that].

When he was telling you his story in the first place, did you picture yourself in it at all?

No. No, no, no. I was just listening to what happened to him.

So you pictured him in it?

Of course.

I always wonder how people envision each others' stories, particularly artists.

I could see everything -- and still do, the way he described it. [Pause] It's interesting how we have a belief system. It prints in you. The first time you hear something, it prints in you forever. That's why when I got the script -- and it was slightly different and there were details I didn't have -- I said, "But remember you told me about that moment? It's not in the script. How come?" He said, "Oh, right I forgot. Well, I made it up when I was telling you the story."

And that's precisely the sense the viewer has in Certified Copy: You never know what's real, even based on some basic fact from a scene or two earlier. A language, a disclosure, a relationship. How does that work on the set?

It was exactly his script. He made up the script. He made up the story. There was some freedom, or doors opening, or some improvising, but it was very, very little. So it as mainly his idea. The way I was acting brought another turn inside the story; he didn't expect me to be so intense on specific scenes, so he ended the film quicker. We dropped three scenes. We shot chronologically. After the restaurant scene, he said, "OK, we're going to end the film here. It doesn't need to be spread out. It needs to resolve in the hotel room." That was my participation: The truth of the acting has to be there, and that was my contribution, in a way.

You've collaborated with some pretty important directors over the years -- Godard, Kieslowski, Haneke, Malle, Assayas, etc. etc. -- with quite singular visions. This project seems more flexible, in a way--

Yes, but that's why I choose them. A real good artist doesn't fear about his power, because he's already powerful. So he's more welcoming, in a way, than a director who's not as talented or has fear about his power -- who's controlling. It's not always the case, though. Haneke is very controlling, but he likes to be surprised sometimes as well. And he has a strong universe. Others are more into being more welcoming: "I want to see your soul, and I want you to feel free to be who you want to be through this character."

Pages: 1 2