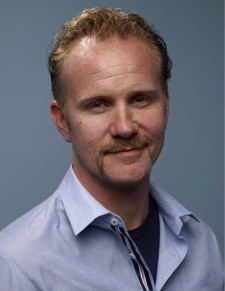

Morgan Spurlock on Freakonomics, Super Size Me's Long Tail, and the Problem With Jamie Oliver

Morgan Spurlock is just one-sixth of the all-star documentarian ensemble responsible for Freakonomics, but he's unarguably the only director in the group who might prompt a double take if you saw him on the street -- "Hey, isn't that guy who did Super Size Me? What's his name?" Which brings up kind of a funny point.

Morgan Spurlock is just one-sixth of the all-star documentarian ensemble responsible for Freakonomics, but he's unarguably the only director in the group who might prompt a double take if you saw him on the street -- "Hey, isn't that guy who did Super Size Me? What's his name?" Which brings up kind of a funny point.

Spurlock's contribution to Freakonomics -- the adaptation of Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner's bestselling book about the "hidden side of everything" (it opens Friday, read Movieline's review here) -- deals with the long-term effect of a person's name on his or her life. In particular, it focuses on data tracking the social and professional progress of those customarily black names (and some not-so-customary ones, including the doomed Temptress and the jaw-dropping siblings Winner and Loser) against those with customarily white names. From strippers to Shaniquas, nobody is spared scrutiny.

It's sensitive stuff handled in quintessential Spurlock fashion -- with humor, visual panache and not just a little volatility. He spoke about his segment of the film (Alex Gibney, Eugene Jarecki, Seth Gordon and Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady directed the other portions) with Movieline, bringing up a few intriguing points about the impact his initial, reputation-making work as well.

So I have to ask: How has the name "Morgan Spurlock" influenced your upbringing and your career?

I'll tell you what was interesting: As a kid, and this probably was an influence on me, there were no other Morgans in my school. There were no other Morgans in my town -- Beckley, West Virginia, where I grew up. I never met another Morgan until I was 16, 17 years old, and I met a little girl on a beach when I heard her mom or dad yelling for her. I was intrigued that there was this little 3- or 4-year-old girl. For me, it was one of those things. Having a name that wasn't like anybody else's did make me feel different, you know? Sometimes in a good way, sometimes in a bad way.

Did you get to choose the segment you wanted?

I did. I chose this one because about a year and a half before this I had a little boy, who's now 3-1/2. His mom and I... The whole name thing was a real conversation. Anyone who has kids will tell you, "Oh, we went through all these names, we were trying to figure out what to name him..." We had a boy name; thank God we had a boy. It was my great-uncle's name: Laken. It was a great family name -- a great, strong name. And then we tried to figure out: If we had a girl, what would her name be? We literally could not come up with a girl name that we liked. "That's too soft, that's too girly, that name's too butchy..." You want a tough-girl name, but not too tough-sounding. We couldn't find anything. So luck had it that we had a little boy.

And that was your inspiration to choose this segment?

Yeah.

I was struck by the visual style -- tracking shots, set-ups and set pieces, etc. Not very "doc-like." How did you settle on this approach?

When we first started talking about this -- my producer and my writing partner Jeremy Chilnick -- I really wanted it to look and feel like a movie. When we went into the section about the characters in the book, I made a conscious decision early on not to chase after Temptress or Winner and Loser. We did them as re-creations. I wanted to shoot them as a film. There was a lot of Steadicam and a lot of real camera moves that made it feel very cinematic. As far as everything else that was marrying through there, I wanted to have a real pop feel to it -- how your name carries you through society.

There was some sort of a bank or investment commercial where people were carrying their nest egg around under their arm. Not that actual egg, but their worth -- the foam numbers? That commercial was running through my head the whole time we were writing the script. I thought, "What if those people who were carrying their numbers were carrying their name? And your name is this thing that's always with you?" So we used that as the model for the named we married to everybody, from the strippers Brandi and Candi to people who were just on the street walking around.

Speaking of whom, those people on the street are integral to the film. How did you want to utilize them, and what kind of resistance did you encounter?

Whenever we do man-on-the-street, people are always surprisingly eager to talk about just about anything. Which is amazing. Seriously. We approached people here downtown, out in Bayside and Forest Hills [Queens], up in the Bronx... We wanted to create a very eclectic blend of neighborhoods and people and ethnicities and have people who would be very honest about what they felt or what they believed. One of the things that I think really comes across in the piece that we made is that you really do see there is a very strong racial divide that very much exists -- and judgments that are based on that racial divide, simply by their names and they represent.

But on the other hand, you avoided the repercussions Asian names or Indian names or... I don't know, French names have on individuals. I was also curious about that.

I think in America it's definitely more about the black-white divide than the Asian-white divide, or the French-white divide. People in America will talk sh*t about French people, but that's not where the initial conflict in the United States exists. I think there is a much stronger black-white divide in the States. The more we shot, the more it came out. There were Asian names we talked about, but that's one of the things we cut out. It felt superfluous.

Why?

Well, there was this section where we talk about Asian names as a piece of it. We're using Roland Fryer's study, which centers much more around black and white names. As does Sendhil Mullainathan's resume study. Sendhil Mullainathan has a fantastic Indian name and is from Harvard; Roland Fryer has a fantastic African-American name and is also from Harvard. But both of their studies focus more on the black-white divide. What I love abut Dr. Mullainathan's study was that no matter how qualified you make Tyrone Washington on his resume, he still wasn't going to more callbacks than Joe Smith, simply because of that moniker.

Pages: 1 2

Comments

It was a very great thought! Actually would like to thank you for the content you have shared. Just carry on publishing this sort of pieces. I most certainly will stay your devoted subscriber. Many thanks.