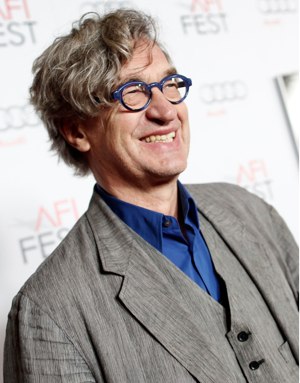

Wim Wenders on Pina, 3-D Epiphanies and Until the End of the World at 20

After more than four decades of creative peaks, valleys, experiments and triumphs that have established him as one of the most eclectic filmmakers of his generation, Wim Wenders has ventured into entirely new territory for his new documentary Pina: 3-D. The film's subject -- the late, legendary choreographer (and Wenders's longtime friend) Pina Bausch -- likely wouldn't have wanted it any other way.

After more than four decades of creative peaks, valleys, experiments and triumphs that have established him as one of the most eclectic filmmakers of his generation, Wim Wenders has ventured into entirely new territory for his new documentary Pina: 3-D. The film's subject -- the late, legendary choreographer (and Wenders's longtime friend) Pina Bausch -- likely wouldn't have wanted it any other way.

Part concert film, part biography and all warm-hearted tribute, Pina profiles Bausch's work and influence both through the eyes of her colleagues and against the backdrop of the world that inspired her. Wenders frames this legacy vividly -- from a stage lined with soil to a somnambulant stroll through the park to a vaguely hallucinatory trip on a hanging commuter train -- while the 3-D technology entitles the dances themselves to the space and dimension that eluded the director over decades of previous attempts to collaborate with Bausch. The results have moved festivalgoers from Berlin to New York and Los Angeles, and they finally reach U.S. theaters this week in limited release.

Wenders spoke with Movieline about Pina, Pina, pushing the limits of 3-D, the 20th anniversary of his great, globetrotting Until the End of the World, and how to enjoy the reviled Lou Reed/Metallica collaboration LuLu.

Pina has caught on quite dramatically since premiering earlier this year in Berlin. What's your take on the reaction -- and having reestablished Pina's legacy onscreen?

I think the reaction by audiences by audiences not only in Europe and America -- but also by critics -- is really a reaction to the beauty of Pina's work. A lot of people have caught on to the film in very emotional ways. I think they are surprised and at the same time happy that there was something they may have missed there, but now they can at least see it right in front of their eyes.

Obviously you and Pina go back quite a ways, but how and when did this kind of collaboration first arise?

You have to go back a quarter of a century. We first started to talk about it in the mid-'80s, and then we just toyed with the idea. We really took it more seriously in the '90s, and it was Pina who pushed for it. As soon as she did, I realized, "We've got to do this." I had to sit down and write out a concept and actually write out how I would do this -- how I would film the glory of Pina's dance. I realized I didn't have, in my craft at least, what it took to make it happen. I felt I didn't have the adequate tools, and the more I thought about it, the less I was convinced I could do justice to Pina's art with my possibilities as a filmmaker. It was the invisible wall between what Pina did onstage and what I could put on the screen. I was honest to Pina and told her, and she was patient with me. She said, "Eventually you will find it. There's got to be a way." And that was a running gag between us for more than 10 years. "When are you ready, Wim?" And I said, "Not yet, Pina." Until I found a way -- and that was not in myself, not in my soul or in my heart. I found out all of the sudden that there was an addition to my craft that I had not known yet. And that was called 3-D.

What was your first reaction to the resurgence of 3-D and its improved technology, particularly as a filmmaker?

I was sitting in a theater putting on these glasses for the very first time... I mean, I'd done it 40 years ago for some Hitchcock movie, but that was long ago. I even remember in the '90s, I saw a Cirque du Soleil film in 3-D. But the technology wasn't really available. So 3-D was altogether forgotten, and it had never really been an option for us when we thought how to do it. And all of the sudden I'm sitting there with these glasses on, not thinking of much, really. I saw a film called U2 3D -- a very early 3-D film, one of the first on the market. I thought it would be fun to watch a 3-D concert. But from the first shot on, I was mesmerized. I almost didn't see or hear the film anymore; I just saw the possibilities. And the possibilities were the answer to 20 years of questioning ourselves how to film dance. There it was, because for the first time we could enter the very kingdom of dance -- and that was space. It hit me that that had been the invisible wall -- that we had never had access to that kingdom.

How did you select the pieces that were most compatible with 3-D? How did you determine they were compatible?

We selected the pieces together -- Pina Bausch and I. Their compatibility with 3-D was striking. In a strange way, Pina's dance and 3-D were made for each other from the beginning. It was like a match made in heaven; it was beautiful, this affinity for each other. From the beginning, I knew they were made for each other, and they would bring out the best in each other. Say, for instance, Café Müller and Le Sacre du Printemps -- the first ones that we chose. Café Müller is a stage full of these chairs and these dancer running through these chairs, and the space itself is so beautifully staggered with these objects -- these chairs -- you couldn't have thought of it in a more ingenious way for a 3-D shoot. And Vollmond (Full Moon), the last piece we shot -- with this water onstage, and all this water coming down and being splashed toward you? It was like it couldn't have been choreographed more nicely for 3-D.

Beyond the dances, though, some of the scenery and logistics themselves are stunning. What went into deciding to shoot on a train or in a traffic intersection?

When we started to shoot that was all wishful thinking, because we started in 2009 -- the infancy of 3-D. There was not much equipment available. The first leg of the shoot we shot on the stage with this huge monster -- this huge dinosaur -- of a crane to carry the equipment. We would not have been able to go into the hanging train or the city; the equipment was not light enough. And to shoot with Steadicam was completely wishful thinking on the first leg. You have to remember this was months before Avatar even came out. You couldn't just rent any equipment. It wasn't available. And then my stereographer realized how badly I wanted to get out into the city, and he singlehandedly created the first Steadicam rig that was available -- at least in Europe -- and with the very first generation of cameras that were mobile, we went out and shot out and about in the city. That was the next spring.

There just seem to be so many onlookers out in the city. Were people curious?

I swear to God, nobody seemed to know what we were doing there. And Wuppertal is an industrial, working-class city. They don't care about some film crew standing on the corner. We were left alone as much as Pina was left alone for 40 years. That's what enabled her to work in that little city and work with that continuity. She was able to work unobserved.

How much of directing itself is in fact choreography? Say, between actors, or with the camera, or with actors and the camera against space?

In the case of Pina, the choreography already existed, and I had to respect it. And I wanted to respect it as much as possible. My choreography was the choreography of the camera -- a sort of reverse-angle choreography: I had to make the cameras sort of react and dance along to Pina's choreographer. So I was a choreographer of the camera. I probably was such a choreographer after my initial meeting with Pina, which was in the mid-'80s. I instantly got high doses of Pina; I was so blown away with everything that was available that I saw a retrospective of six in a row, and that was, of course, not quite an overdose, but definitely mighty doses of Pina Bausch that really changed my life. And the first movie I did afterwards was Wings of Desire, which by any standard was the most choreographed film I ever made. There was a circus, a trapeze artist... It was a very choreographed movie.

Pages: 1 2