At NYFF: Martin Scorsese Gives Hometown Crowd a Taste of 3-D Hugo

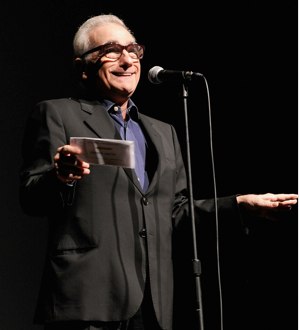

After a weekend of speculation, guesses and second-guesses about which top-secret "work in progress by a master filmmaker" would in fact screen tonight as a last-minute addition to the New York Film Festival, Martin Scorsese confirmed today's reports by taking the stage at Avery Fisher Hall in Manhattan and introducing his family-friendly 3-D opus Hugo to a loving hometown crowd.

After a weekend of speculation, guesses and second-guesses about which top-secret "work in progress by a master filmmaker" would in fact screen tonight as a last-minute addition to the New York Film Festival, Martin Scorsese confirmed today's reports by taking the stage at Avery Fisher Hall in Manhattan and introducing his family-friendly 3-D opus Hugo to a loving hometown crowd.

Not everybody in attendance had monitored the buzz around tonight's event. A few wizened viewers who probably couldn't distinguish the output of a stereoscope from that of a stereophone looked baffled as ushers issued fistfuls of plastic-wrapped glasses with their seating directions. ("What are these? "They're for the 3-D." "Row 3-D?", etc. etc.) But most of the house settled in with the type of anticipation befitting any never-before-seen Scorsese film, let alone a crowd-pleasing gambit applying the premiere moviegoing gimmick of our day to a product that even the filmmaker admitted beforehand wasn't quite finished yet.

"So this is a work in progress," Scorsese said from the stage, his right hand raising a slip of paper containing Hugo's inventory of unfinished elements -- which he commenced to read. Like, all of it. "Which means it's not color-corrected. We're starting that right now. At the beginning of the film and in other places there are things called pre-visualizations, which means they're little, crude, computer-generated people, which they promise me are going become human soon. The visual effects are temporary. The 3-D is still being worked on, and the sound mixes are temporary. The music for the most part is still temporary. That means it's an actual score but it's on temporary instruments. He's recording it now in London -- Howard Shore. The credits are 2-D, and there aren't that many on there right now. And you will see a few wonderful green screens. You can put in anything you want.

"So look!" he concluded. "I hope you enjoy it, and I hope that those of you who do like it come and see the final film."

And that's basically to say that the story is here to stay, for better or worse. Which is fine by me; I quite enjoyed Hugo for the most part, if only for its singular status as the world's first activist magic-realist holiday family blockbuster-hopeful. (I think? Was there some ice-cap preservation angle to The Polar Express? I never saw it.) Scorsese and his Aviator screenwriter John Logan have adapted Brian Selznick's acclaimed novel-comic hybrid The Invention of Hugo Cabret as a pure tribute to not only cinema, but also the endangered legacies of its earliest practitioners. As Selznick did, Scorsese lathers the pill in generous coats of aesthetic sugar and bottles it in the story of Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield), a young orphan whose primary, essentially accidental purpose in life has become to wind the clocks in a vast Paris train station circa 1930.

Chased endlessly by a war-veteran station inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen) and eyed with suspicion by a tired old toy-booth owner (Ben Kingsley), Hugo scurries and sulks around the premises by day while attempting to fix a wind-up automaton discovered by his late watchmaker father (Jude Law). Its Mona Lisa smile teases Hugo and is even occasionally reflected in the face of Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz), a more privileged orphan looked after by the toy-booth owner and his wife, Isabelle's godparents. The kids make fast-ish friends whose bond over Hugo's confiscated automaton notebook takes deeper root in the lure of cinema and the quest for belonging.

A conventional festival review from this point would just be inappropriate; there are currently green-screen backgrounds visible in numerous shots and entire sequences of train commuters that wouldn't be too out of place in a Taiwanese news animation, and anyway, Stephanie Zacharek will do the honors when the completed Hugo reaches theaters this Thanksgiving. Let it suffice to say that Scorsese, mining the innovations of his filmmaking forebears and contemporaries alike, runs his typically adventurous camera through the 3-D ringer with aplomb. His introduction -- comprising a whooshing tour of the station, a hungry pursuit by the game, gimpy Baron Cohen and his equally game Doberman, and finally a gorgeous perspective on winter lowering over Paris -- is a thing of nearly wordless beauty. A sturdy first act gives way to the marshmallow center of the story, stalling out like Hugo's stubborn automaton yet never swinging its sentimental hammer with lethal, Spielberg-grade force. Stray diversions come and go, some in the forms of plot points (wait, Hugo's father died how?), others in the forms of such humanizing devices as Emily Mortimer, appearing as the flower girl whose heart is the inspector's only objective sought more desperately than Hugo himself. Christopher Lee, Richard Griffiths and Frances de la Tour orbit the scene in various other permutations of gravitas.

But then Scorsese gets serious. Those familiar with Selznick's source material will understand the allure of Hugo Cabret for the filmmaker, with their mutual passions for cinema as both mass entertainment and cultural heritage. Those unfamiliar shouldn't have the specifics spoiled for them, save to say that the final 30 minutes are a captivating tightrope walk that evince both passions without guile or reservation. It's so over-the-top that many exiting theatergoers broke their smiles only to either admire or rue Scorsese's whimsical evangelism. "It was so preachy!" I told one peer, only to realize before adding, "But I kind of liked being preached to!" At least I preferred it compared to the well-made, well-acted but relatively bloodless conviction of the film's first half.

In any case, I'm nothing if not eager to follow directions, especially those from the evening's master filmmaker. Surprises are fun, but the jury is out. Second viewing, here I come.

[Top photo: Getty Images]

Comments

Shame he wasted a year making a kids movie. There, I said it.