On DVD: What Reality TV Could Learn From Crumb

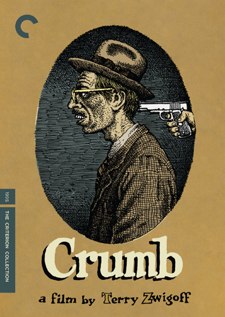

Truly, reality TV is too timid a whore to tackle the real American dysfunctional family -- the kind that breeds crime and weird sexual compulsions and suicides in cluttered, unkempt houses on the not-so-hot side of town. I knew kids that came from those families, and chances are so did you. No, for this you need an indie documentary, and Terry Zwigoff's famous, acclaimed Crumb (1995), now out in a tricked-out package from Criterion, may be the best film ever made about that creepy edge of American life.

Truly, reality TV is too timid a whore to tackle the real American dysfunctional family -- the kind that breeds crime and weird sexual compulsions and suicides in cluttered, unkempt houses on the not-so-hot side of town. I knew kids that came from those families, and chances are so did you. No, for this you need an indie documentary, and Terry Zwigoff's famous, acclaimed Crumb (1995), now out in a tricked-out package from Criterion, may be the best film ever made about that creepy edge of American life.

Not that it's only about Robert Crumb's family, it's also about Crumb himself, the country's most popular and notorious underground comic artist in the '60s but by now an unlikely cultural institution, regularly honored and ensconced in the pages of The New Yorker. (A few decades ago, The New Yorker wouldn't publish Crumb any more than it would've featured a centerfold.) The transformation is partly the film's doing, nudging Crumb's reputation out of the perpetual-adolescent stink-bowl where it had been, and been beloved, for so long, and onto the revered-elder-statesman phase. Zwigoff's film hardly shrinks from either Crumb's achievement or his controversies, which are pretty much the same thing -- it's almost impossible not to admire Crumb's cartooning skill, obsessive draftsmanship or wit, and at the same time be appalled by his drawings' vaginal journeys, incest jokes, hypertrophied breasts, sexual mutations, masturbatory fantasies, etc. At their most delicious, Crumb drawings can be outright sickening, if only because you're left wondering what unconscious little knot of hatred the artist is working to untie.

But if this were just yet another portrait of a famous and/or neurotic comic artist, no one would've cared. As it is, both Crumb and Zwigoff had the nervy good sense to explore Crumb's family -- his shut-in brother Charles (who was the original comic-book genius), his weathered and philosophical brother Maxon (looking like a cross between Richard Widmark and Skeletor), his mother (lost in her own sub-working-class, old-age craziness), and the memories of the Crumb patriarch, who by all accounts was an abusive prick. The picture we get, through stories and old photos and comics the boys made on their own, is clear: public weirdness, ceaseless masturbation, alienation, parental neglect, years passing out of step with society, warped psychological directions that might not have proper names. The present day state of things is only much, much worse - you can smell the urine in the bedclothes.

This onion-peeling goes on to a very uncomfortable degree, and we shouldn't be blamed for thinking that maybe the film itself is another one of Crumb's taboo-busting maneuvers. Why else would he expose his hapless kin to the world like this, except to free himself? (He does the interviewing himself, leaving Zwigoff, an old friend, behind the camera.) At Sundance and in theaters in 1995, Crumb stood beside Ed Burns's hailed debut The Brothers McMullen, which still scan like good and evil versions of the same mad-family movie: three dysfunctional brothers with a dead-but-still-hated bully of a Dad wrestle with women and their own twisted psyches. The upshot by the end of Crumb is: one brother famous, one lost, one dead. No wonder the two Crumb sisters, Sandra and Carole, had the good sense to steer clear of the film altogether.

The Criterion edition comes loaded with two audio commentaries (one with Zwigoff, one older track with Zwigoff and Roger Ebert, a big fan), almost an hour of unused footage, an essay by critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, booklet artwork by all three brothers, and a vintage repro of 12-year-old Charles's Famous Artists School "talent test," the likes of which that infamous kid-scam outfit could not have seen before.