On DVD: ...But I Know What I Like

What is art for? Art with a capital A -- should it be measured only as a "pleasure" delivery system, as New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl rather lamely contends, or does it represent a higher purpose, a public good, a high-water mark of human achievement? Or is it just a business, a marketplace run on run on vaporous critical judgments? Or some morph of the above?

Don Argott's acclaimed new doc The Art of the Steal comes with these questions shooting out of it like hot popcorn, without meaning to. In a way, the film's attitude toward art -- so seductive to culture-craving, middle-class, middle-aged audiences otherwise underserved in the mass-media slipstream -- is part of the problem it decries so feverishly.

The matter at hand is the Barnes Collection -- the biggest and most valuable cache of art you've never heard of. Someone in Argott's film estimates that the Barnes's massive aggregate of Renoirs, Picassos, Van Goghs, Cezannes, et al., collected during Impressionism's heyday by a drug developer/magnate, is worth so much no individual or corporation could buy it -- maybe a nation could. It's not an art collection, but the art collection. No museum in the world can come close -- and Barnes's will maintained that the whole kit and kaboodle be stationed without change in the building he built for it in suburban Pennsylvania, and that it be used for educational purposes, not as a profit-making public museum.

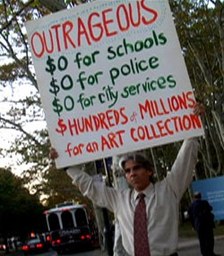

Barnes's will had the rule of law behind it, but, as Argott details graphically, when you're dealing with a resource worth as much as $35 billion or maybe much more, the law (and virtually any other human concern) becomes subject to the weathering of greed, politics and power. Which is what has happened: The Barnes Collection became the prize in a decades-long struggle where various politicians lied, propagandized, campaigned and connived to get control of the art, move it to Philadelphia, and begin minting money from its exhibition.

The details of the fight are sometimes absurd (a black politico accusing his adversaries of being like the KKK, etc.), and many of the protagonists reveal themselves to be outright tools. But the larger questions begin to nag, as it becomes clear that Argott's position is that Barnes, who died in 1951, was some kind of paragon of anti-institutional principle (he hated the art-world elites) and that the limitations he put on the collection's use are by themselves pure, righteous and meaningful.

They're not, really. The undisputed legal legitimacy of the Barnes will notwithstanding, it doesn't really matter to the art itself if it's rarely seen in a suburban building or if it's seen by millions in Philadelphia. And Barnes is still dead.

They're not, really. The undisputed legal legitimacy of the Barnes will notwithstanding, it doesn't really matter to the art itself if it's rarely seen in a suburban building or if it's seen by millions in Philadelphia. And Barnes is still dead.

Argott's talking heads divide between self-serving politicians, who care nothing about art, and Barnes acolytes, who care little, it seems, about the art-seeking public. The sheer size and valuation of the art seems to get everybody's blood up, and the basic issue -- of where the art will hang and how many people will or should be able to see it -- is blown out of proportion. Barnes didn't want the art he owned to become museum fodder, because he hated the museum culture.

But after he's long gone, what fabulous hurt does it do? What's more vital, a dead man's acrimony, or the relationship between classic art and the public?

Argott's film is very rock 'n roll -- almost incongruously so. It's assembled and jazzed up as if it were detailing a political catastrophe that actually impacted people's lives. But art is what we make of it, how much we'll pay for it, and how much we want to look upon it. That's all. Argott's concerns rest, it seems, with Barnes's rebel yell, not with any particular passion for the paintings. Argott himself has profited from the Collection and its fate, so The Art of the Steal stands in a good inch of composted hypocrisy.

EARLIER: Moment of Truth: Art of the Steal Charts the Biggest Heist You Never Knew About