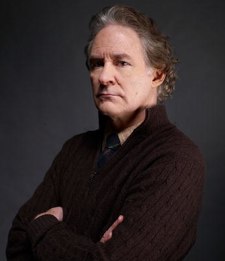

Kevin Kline on The Extra Man, Acting Thieves, and His Possible HBO Future

In the sense that Kevin Kline's legendary range avails viewers to a succession of diverse, unusual roles, The Extra Man is pretty much a typical Kevin Kline film. Surprising, poignant and funny, the adaptation of Jonathan Ames's novel features the Oscar-winner as Henry Harrison, a downmarket Upper East Side dandy whose key to securing affluence is to offer himself as a date to older, wealthy society women. Enter Louis Ives (Paul Dano) a would-be Fitzgerald whom Henry takes into his apartment and under his wing -- with reliably unpredictable and uncouth consequences.

In the sense that Kevin Kline's legendary range avails viewers to a succession of diverse, unusual roles, The Extra Man is pretty much a typical Kevin Kline film. Surprising, poignant and funny, the adaptation of Jonathan Ames's novel features the Oscar-winner as Henry Harrison, a downmarket Upper East Side dandy whose key to securing affluence is to offer himself as a date to older, wealthy society women. Enter Louis Ives (Paul Dano) a would-be Fitzgerald whom Henry takes into his apartment and under his wing -- with reliably unpredictable and uncouth consequences.

Opening Friday, Extra Man packs Kline's prodigious theatrical gifts and his underrated knack for physical comedy into one scrappy bundle. His chemistry with Dano elevates both actors to rare heights, few more dizzying than their slow burn through the culture of "extra men" clinging to the good life by any means necessary -- until they realize it's right in front of them.

Kline spoke with Movieline about the Henry Harrison's anachronistic New York, why the best free-form choreography might be none at all, and what he might be up to soon with the folks at HBO.

I know this is the question everyone starts with, but I promise to mix it up from here: What specifically drew you to this role?

[Affects a whisper] Isn't it obvious? No, you're right. That is the first question, but at least it's not, "What drew you to that role? Why would you want to do that?" This one is just so juicy. It's well-written, and even though to play a wildly eccentric character is not a new type, I think he transcends the type. I think he's an eccentric's eccentric in a way. He's unique, he's particular. The cliche of the eccentric is exploded here. He's so wonderfully... extravagant and outlandish. But I just love his spirit, which is this indomitable, Nietzsche-esque life force. Nothing is going to destroy him.

He seems to be living in a certain era of New York society, but I was never sure which one. What was your impression?

It's funny, because several people told me when they see a cell phone come out, they go, "Wait a minute..." There's a sense it's [old New York] even though it's contemporary. It takes place now. The novel is set in the '90s during the Clinton Administration. It feels like a period film, and I think that's because they very cleverly created this kind of bubble that Henry and Louis have invented for themselves -- that life shouldn't be about the vulgarity and crassness of what Henry sees around him. He wants to erase and crate his own environment. There are so many areas -- the whole confessional transparency, the crazed ethos of today... He prefers the opacity: "The less you know about me the better." There's a mystique. I don't know if you saw piece [recently] in the Sunday New York Times about Greta Garbo and that lost age -- it was by Ben Brantley, the theater critic. It's about the era of old Hollywood and creating a mystique and not talking about your latest stint in rehab -- not being stalked and gawked by paparazzi in your every move.

That's interesting, because there's a lot of speculation about Henry's back story by other characters in the film. How much of the back story you developed was informed by what those characters thought -- if any?

In the book, of course, there's more extrapolation, but there are always unanswered questions. I think there's enough reliable information because it does come from others. There's one woman who says, "He's a gifted writer, but unfortunately very rude." The scene around the table in the Russian Tea Room: "He had his heart broken by a woman." He was a Protestant, but now he's a Catholic; he wants to give all his worldly belongings -- all three of them -- to Catholic charities. But it's a snobbish thing that had something to do with this woman who broke his heart. Or is he gay -- but "gay" of a certain period where if you're gay, just ignore it and don't do anything about it? Now that homosexuality has been politicized, you either have to be out or you don't. When I did In & Out, I was asked "Do you believe that everyone should have to be 'out,'" and I said, "No!" In that way I'm like Henry Harrison: Whatever your sexual preferences are, whatever you decide to do in your own mind or bedroom is your business.

I miss mystique. I miss mystery. I think we live in the too-much-information age. And it's indiscriminate information. What is to gained by knowing that? Especially when it's an actor. Actors should be kind of mythical. The less you know about them the better, the more you can believe that they're Hamlet or Henry Harrison or whomever.

What about the history of a part? Take Hamlet, or Cyrano de Bergerac. How does a part's performances over the years influence how you interpret a character?

Interesting question. [Pause] Sometimes I play roles that I've seen a dozen different renditions of -- enough so they kind of cancel each other. You either steal judiciously from other performances that have resonated for you and eschew what doesn't. When I did Richard III, I spent the first week trying to forget Olivier's performance and trying to quote-unquote make it my own, because you have to. But if there are certain things that have worked so well, and if it resonates -- if you can make something another actor did a matter of historical record -- that's a good thing. It's more of a question in Hamlet or King Lear than anything, really. There are so many different theories, but ultimately what it comes down to are the exigencies of putting on a show. What works for me? What works for this production, with these other actors, on this set, on this night, in this moment? The problem with Shakespeare is that a lot of literary scholars approach it as literature, but theater practitioners look at in a totally different way: He didn't write this to be pored over at leisure. This is for a show to be put on for one night.

Well, Henry has a play -- his self-described masterwork -- stolen. Can an actor have his or her work stolen?

Sure, but I think it's a compliment. It's emulation. I saw Hamlet once, and I thought, "This guy saw our production, because he's stolen... not acting things, but certain costume things, certain period things. I guess I wouldn't say "stole." Maybe "borrowed." I did a production of Hamlet that was quasi-modern dress. Why? The budget. Because if we did it in Elizabethan garb it would have been cheesy Elizabethan costumes. Better to get good versions of a more contemporary [style]. And also because Shakespeare, when he did it, he did it on a bare stage -- which is how I directed it -- and he used contemporary clothes. Little pieces of this and that might suggest a period. Olivier did Hamlet the film in black and white. Why? Because he was having a row with Technicolor. In retrospect, though, we say "Black and white! That's the only way to do Shakespeare. Black and white is not real." Shakespeare's not real! People don't talk like that! It's not natural! But as I say, when you're doing those parts, it's what works for you.

Pages: 1 2

Comments

Wouldn't he be amazing as Damages' villain next season? Honestly, I'd be happy if he'd just do more of anything.

Ah yes, I'd forgotten that Falstaff quote. Thanks for the reminder!