REVIEW: A Bogeyman Gets His Close-Up in Cropsey

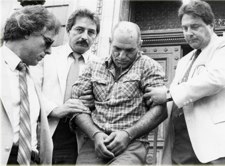

"What do you have to say to the Staten Island community?" a reporter asks accused child murderer Andre Rand about halfway through Cropsey, an absorbing and openly personal look at the function and dysfunction of local legends. "They're the perpetrators of a fraud," Rand replies, before ducking into the armored van that will take him back to Rikers Island. They are the first words he speaks in the film -- a menacing voicemail is his only follow-up -- and they resonate throughout the rest of a documentary that gets a little lost within its own agenda of separating "the facts from the folklore."

"What do you have to say to the Staten Island community?" a reporter asks accused child murderer Andre Rand about halfway through Cropsey, an absorbing and openly personal look at the function and dysfunction of local legends. "They're the perpetrators of a fraud," Rand replies, before ducking into the armored van that will take him back to Rikers Island. They are the first words he speaks in the film -- a menacing voicemail is his only follow-up -- and they resonate throughout the rest of a documentary that gets a little lost within its own agenda of separating "the facts from the folklore."

The film's title refers to an urban legend apparently known to Staten Islanders: An axe-wielding (or alternately hook-handed) bogeyman known as Cropsey was said to troll the woods looking for disobedient children; over time his name became a shorthand for all manner of evil. The filmmakers, Staten Island natives Barbara Brancaccio and Joshua Zeman, were inspired to pick up their cameras and raid untold canisters of archival news footage by the 2004 charges that brought Rand -- who was already serving a 25-year sentence for the kidnapping of a young girl in 1987 -- to trial for the 1981 murder of another local girl. Soon several more cases from the '80s involving missing children were under scrutiny. "The urban legend had come true," claim the filmmakers, a problematic overstatement that casts a shadow of bias over what is to come: While it makes for a great marketing pitch, the actual truth of what happened -- supposedly the central concern of the film -- is almost impenetrably complex.

The directors return to the Willowbrook, an abandoned children's mental institution where Cropsey was said to roam (and where the homeless Rand actually lived, after briefly working at Willowbrook), to scan the grounds with giddy unease and recount their memories of the myth. The letters that Rand later sends them are received and pored over with the same junior-detective breathlessness: At times their "investigation" comes across as an adult enactment of the game of bogeyman that haunted their freaked-out kiddie dreams.

Which is not exactly a slam: Zeman and Brancaccio structure the film as a sort of homemade murder procedural, where pavement-pounding crowd-sourcing proposes an alternative to the modern cold-case staple of DNA evidence. Interviewing everyone from the arresting officers and victims' parents to neighborhood kids and Rand's old Willowbrook cronies, they craft a kind of word-of-mouth collage to fill in the blanks of both Rand's story and those of the murders themselves, which are many. Rand was convicted of kidnapping (but not murder) on circumstantial evidence. His Cropsey-friendly profile put him in jail the first time; will it go two for two?

Although their "it takes a village" approach initially seems effective -- after all, it was community members, and not police, who eventually found the first body -- its limitations soon make themselves clear. Police detectives and local tongue-waggers alike veer into rumors of Rand digging up and copulating with graveyard corpses; the inevitable satanic cult accusations lead the filmmakers to a paranoid sect of pseudo-Christians. In recalling the devil-worshipping accusations leveled against the West Memphis Three (whose specious child-murder trials are documented in the Paradise Lost films), this development suggests that isolated communities and satanic cults seem to exert a sort of magnetic pull on each other. Instead of questioning that co-dependency, Zeman and Brancaccio succumb to it, descending into Willowbrook at night in an indulgent and yet rattling digression.

While his prior child-molestation conviction is deeply troubling, and his unnervingly meticulous letters -- each printed character pressed over twice with a blue pen -- are those of a straight-up madman, Rand is also a perfect scapegoat. In a casually inflammatory rant, a former reporter claims that a scapegoat is exactly what Staten Islanders like best; he evokes the para-medieval mentality that governs an island known -- even to its inhabitants -- as an anything-goes dumping ground. Again, rather than delve further into the black heart of such accusations, the directors skim the surface just long enough to further a less satisfying and more obvious purpose -- that of asserting the impossibility of truth.

Ultimately -- and perhaps fittingly -- Cropsey is most effective as a study of Staten Island and its inhabitants, specifically the half-life of grief as it is manifested in a self-contained community. Of the five missing children, only one body was ever recovered, a source of abiding, primal torment for the families. "I could forgive him if he returned the remains of my sister," says one police officer. Just a boy when she disappeared, his whole life has clearly been directed by her loss. Another father finds himself distinctly underwhelmed by a legal triumph and decides that closure is "a bullshit word." In his next breath, however, the possibility regains its grip: "I'd just like to find her remains, and put it to rest." If there is a truth to be found in this involving, slightly involuted film, it is in that moment: Surely the pursuit of justice has no more human form than a father's unyielding determination to properly mourn his child.