There's a moment at the end of Gavin O'Connor's MMA drama Warrior in which two men who have been relentlessly beaten and pummeled in the octagon stand dripping with exhaustion, rivers of sweat mingling with the tears running down their faces. It doesn't matter that you can't tell the sweat from the tears; that's partly the point of Warrior anyway, which makes you feel every emotional wound just as acutely, if not more so, than the bruising, rib-crunching body blows. Yes, this is a mixed martial arts movie (distributed by genre specialists Lionsgate, no less). But it's also one of the most heart-wrenching and deeply felt films of the year.

That's not to say Warrior falls all the way into the tried-and-true-and-overdone terrain of "inspirational sports movie," although it does wade through its fair share of genre clichés and calculatedly affecting storytelling tropes. It's Rocky redux in a sense, an underdog fighting tale set against the backdrop of working-class America.

The key difference is, in Warrior there are two Rockys. Brendan Conlon (Aussie Joel Edgerton) is a high school physics teacher in Philadelphia struggling to keep a roof over the heads of his wife (Jennifer Morrison, in an exquisitely balanced supporting turn) and their two young daughters following a mortgage-draining medical crisis. When bouncing on the side doesn't quite bring in enough cash to keep them afloat, Brendan goes back to the pre-teaching gig that pays well but risks doing damage, both physical and marital: Arena fighting at the local strip club.

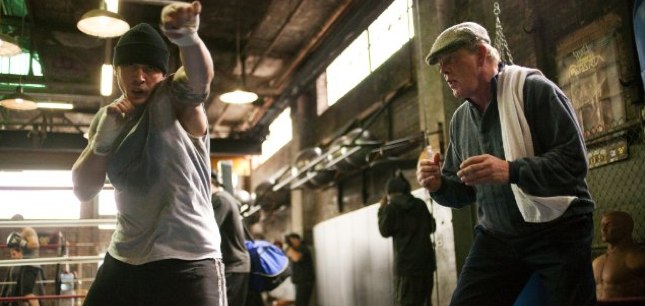

Meanwhile, over in Brendan's hometown of Pittsburgh, his estranged father, ex-alcoholic and formerly abusive wrestling coach Paddy Conlon (Nick Nolte), comes home from a 12-step meeting to find his long lost other son Tommy (Tom Hardy) on his stoop. Tommy's more of an enigma, to his father and to the viewer; self-destructive, closed-off, and bitter over a past family rift that goes unspoken, he's running from something he won't share with anyone. A chance opportunity at the local gym gives Tommy the break he's been looking for -- entry into an internationally-televised mixed martial arts tournament called Sparta, with a $5 million cash prize to the last man standing.

And so we launch headlong into the road to Sparta, following both Conlon boys as they wallop and wrestle their way toward the championship, and -- of course -- toward the inevitable brotherly showdown in the ring. Their shared history, gathered in snatches of pained conversation over the course of the film, explains why a rift remains between them and their reformed, lonely father -- and also why it's so damn hard for these men to forgive the wrongs of the past, as remembered differently by each through the haze of memory and hurt. Paddy, at least, has come the farthest from that tumultuous family history, but then he's also the cause of it all. The realization consumes him, reflected in his obsessive reliance on an on-the-nose but fitting book-on-tape cassette of Moby Dick.

But despite Paddy's efforts at reconciliation (and a heartbreaking scene in which Nolte's Paddy, rejected for the umpteenth time by Hardy's Tommy, falls off the wagon in the most devastating way -- just one of Warrior's surprising, award-worthy moments), this is Brendan and Tommy's story. One's lithe and composed, strategic, a family man; the other brawny and explosive, driven by pain, a loner -- two sides of man and masculinity, deep readers might note, struggling to reconcile against all odds.

O'Connor, whose 2004 Disney hockey pic Miracle similarly used convention and cliché to great emotional effect, overcomes the obviousness of Warrior's set-up in the best way possible: By making his archetypes into fully fleshed out characters who could conceivably carry their own individual Rocky Balboa-like stories. (Look for O'Connor in a cameo as the gazillionaire MMA enthusiast who funds the central tournament.) The dual-focus narrative, used extensively in film musicals and romance tales to make us yearn for two opposing figures to unite, works well here applied to this broken family unit even if it risks succumbing to corny convention every now and then. Even with its own Ivan Drago figure in the form of pro wrestler Kurt Angle (one of a handful of real fighters tapped for the film, including MMA fighter Erik Apple) as a silent Russian champ named Koba -- who is, refreshingly, not written as some incarnation of evil for our heroes to rally against but a totally reasonable, if stone-faced, wall of muscle -- Warrior's real villain is the specter of the past, a cocktail of bitterness, misunderstanding, and hurt that never healed.

Warrior will draw comparisons to last year's multiple Oscar-winner The Fighter, another story of dueling brothers coming to terms with each other in the world of combat sport. I'd argue that Warrior is the more affecting of the two, partly due to the fact that The Fighter is based on a true story, whereas the fictional Warrior is able to strip down to the basics of storytelling, building characters that conjure and carry ideas with them along the way. The Fighter is a great true tale/inspirational sports movie, but Warrior is good, old-fashioned storytelling that epitomizes exactly why certain conventions became conventions in the first place. And the MMA element, a curiosity at first, adds something that no boxing tale we've seen before has: The metaphorical tap-out and what it means to swallow one's pride and submit to love, as opposed to triumphing by the sheer force of a K.O.

Still, it's the cast that elevates Warrior to greatness, led by Hardy's turn as the violent, wound-up Tommy. Ever since breaking out in Nicolas Winding Refn's Bronson, in which he played a real-life prison brawler in yet another wholly physical but vastly different performance, Hardy's star has skyrocketed; cast in Christopher Nolan's Inception and in the now-filming The Dark Knight Rises, the British actor is undoubtedly having a moment. Here he is a wounded child living in a Marine's body, skulking about like a feral animal ready to claw at whoever comes near. He's so damaged he must be broken by love, using the physical, fist-to-fist language of bruisers and hard men. The sight of Hardy, tattooed and muscled and drenched in blood and sweat, struggling against his instincts, in agony from years of pain and abandonment, weeping with his brother while the world watches unaware of what's really going on inside the ring -- it's the most beautiful image I've seen all year.